March 20, 2012 marked the 160th anniversary of the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Connecticut commemorated this anniversary with a 24-Hour Reading of Stowe’s groundbreaking novel. The event also included a screening of the 1902 silent film adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and a discussion led by Adena Spingarn, a doctoral student at Harvard University.

Please enjoy this piece written by Adena Spingarn as we commemorate this anniversary week!

At the end of 1852, less than a year after the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the New York Literary World described Stowe’s novel as “a phenomenon in the literary world, one of those phenomena which set at naught all previous experience and baffle all established and recognized principles.”[i] In the first year of its publication, Uncle Tom’s Cabin had sold a record-making 300,000 copies in the United States alone, the equivalent of close to 7 million copies in today’s market. (The number becomes even more impressive when one considers that each copy is estimated to have had 8 to 10 readers. [ii]) And these unprecedented domestic sales paled in comparison to the international figures: first-year sales reached close to one million between the United States and Britain, with more copies sold all over the world as translations came out.

From the beginning, the astonishing success of Uncle Tom’s Cabin mystified critics, who often posed some version of the question asked by Christian Parlor Magazine a few months after the novel’s publication: “What is in it to make it so wonderful?”[iii] But explaining the novel’s instant and enormous popularity requires a look at more than its text. The Uncle Tom’s Cabin phenomenon that made Uncle Tom a household name came out of a perfect storm of factors both within and outside of the novel. With almost preternatural timing, Uncle Tom entered a world that was singularly poised for the massive circulation of his image and a society that had just become ready for him.

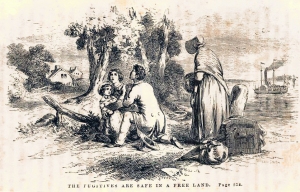

With the recent passing of the Fugitive Slave Law (part of the Compromise of 1850), slavery had taken on an increasingly central role in American political life. The law required all Americans, even those living in states where slavery was illegal, to help return runaway slaves to their masters. United States marshals and deputy marshals who refused to do everything in their power to capture a fugitive slave would be fined one thousand dollars, and if a fugitive escaped under the marshal’s watch, he was liable for the slave’s full value. Any person who obstructed the arrest of a fugitive or attempted to help a fugitive in any way—even by providing food or shelter—was liable to a one thousand dollar fine and imprisonment for six months.[iv] Thus, Northerners who had been content to leave the slavery issue to the South were now forced, to their distress, to become an active part of it.

Stowe herself was indignant about the Fugitive Slave Law, writing to her sister that it made her feel “almost choked sometimes with pent up wrath that does no good.”[v] Shortly after its passage, when another sister wrote her a letter urging her to use her talent for writing to help the nation understand the injustice of slavery, Stowe realized that fiction could be a way for her to channel her righteous anger into something productive. Upon reading the letter in the parlor one evening, she stood up and declared to her children, “I will write something. I will if I live.”[vi]

At the same time that Americans were becoming more receptive to an anti-slavery message, new technologies promoted the uniquely rapid spread and wide embrace of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Cost-saving technological advancements in printing made books available to a much larger audience of readers than before. The steam-powered Adams Power Printing Press, patented in 1836, enabled much faster production of books, and therefore drastically reduced their cost. With the invention of stereotyping in 1811 and electrotyping in 1841, new editions of books no longer required the re-setting of type. Publishers could make permanent, relatively inexpensive metal plates and store them for subsequent editions. Other technologies that aided book production included two paper-making machines that came into widespread use in the 1830s: the belt-based Foudrinier (1799) and Thomas Gilpin’s cylinder (1816). By allowing the production of continuous rolls of paper in large widths, these machines offered a significant savings of time over sheet-by-sheet printing.[vii]

Technological advancements outside of book production also promoted the wide circulation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Beginning in the 1830s and continuing until the Civil War, an enormous boom in the building of railways spread railroad tracks across the United States, connecting what had been regional publishing networks into a growing national print culture. Because the railroad network was clustered in the Northeast, publishers and authors could and did ignore the preferences of Southern readers in favor of Northern markets. Improved and cheaper domestic lighting and wider availability of eyeglasses also expanded the hours for reading and made it easier to sit down with a book.[viii]

Entering this growing national literary marketplace, Uncle Tom’s Cabin also benefited from the unusually canny and extensive promotional strategies of the novel’s first publisher, the small Boston firm John P. Jewett and Company. Boston’s leading publisher, Phillips, Sampson, and Co., had already rejected Stowe’s serialized novel, one partner holding that an anti-slavery novel serialized in an abolitionist journal “would not sell a thousand copies”—clearly a monumental misjudgment.[ix] But Jewett’s wife, who had started reading the serials of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the National Era, urged her husband to publish it, insisting that it would sell well. Before a third of the novel had been serialized, Jewett wrote to Stowe and secured a contract with her to print Uncle Tom’s Cabin, not yet knowing how long the novel would eventually become.

An unusually savvy marketer, Jewett both capitalized on existing publicity practices to promote Uncle Tom’s Cabin and developed effective new ones. With a prophetic understanding of the power of advertising, he ensured extensive coverage of Stowe’s novel before its publication by spending thousands of dollars sending advertisements and prepared notices about the novel to magazines and newspapers. Following the custom of the day, these publications would print Jewett’s notices as editorial matter, with little or no amendment, as a kind of compensation for purchasing advertising.[x] Though Jewett’s firm was small and had limited resources, he advertised as much as firms more than five times the size of his own, and he did so with greater acuity. While other publishers tended to advertise a different title in each issue of a journal, Jewett repeated a single advertisement in several issues, building interest over time.[xi]

But Jewett’s real innovation came once the novel was in print, in his sophisticated and ahead-of-his-time understanding that the choice to buy something was as much a social decision as a personal one. In paid advertisements and prepared notices, Jewett went beyond the usual advertising practice of informing consumers about the content and quality of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. More importantly, he stressed the novel’s immense success, going into detail not only about its record sales figures but also the complicated logistical demands of printing so many copies. By handling the novel’s success as itself “an unprecedented event, a publishing phenomenon,” Jewett’s promotional strategy built on its own success, using past sales to promote future ones.[xii]

One of Jewett’s reports, reprinted in The Liberator and The Independent, among others, announced that the publishing firm was having trouble meeting the high demand for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, despite keeping three papers mills and three Adams power presses running 24 hours every day of the week except Sunday. Within three weeks of the novel’s publication, 20,000 copies had sold.[xiii] By May, The Independent reported, 125 to 200 bookbinders were constantly at work binding 90,000 pounds of paper into 55 tons of bound volumes.[xiv] By June, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was in such high demand at New York’s Mercantile Library that the library purchased 45 copies, which remained in constant rotation among the city’s future merchants.[xv] A few copies of the novel even found their way across the country to California, where miners paid 25 cents to take their turn at reading it.[xvi] By reading about all of the excitement over Stowe’s novel, consumers were more likely to be swept up along with it. Jewett, the first publisher to so heavily emphasize these kinds of facts and figures, anticipated what has become common knowledge in contemporary publishing, where magazines and mass-market trade books often trumpet numbers on their covers (“10 Ways to Cut Calories,” People magazine’s “50 Most Beautiful People,” The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People). Though splashing numbers on the covers of magazines often makes for a cluttered appearance, it is so effective in boosting newsstand sales that magazine publishers often embrace the tactic, while opting for a simpler version of the cover for the subscribers who have already purchased their copy in advance and therefore don’t need to be convinced. [xvii]

When sales of Uncle Tom’s Cabin began to level towards the end of 1852, Jewett responded by coming out with a cheaper “Edition for the Million,” which helped sell more copies of the novel after the upper end of the market had become saturated.[xviii] And with sales of that edition calming by the end of 1853, the following year Jewett published Stowe’s Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Although the Key was explicitly positioned as a defense of Stowe’s account of slavery, it also, and perhaps more importantly, kept Uncle Tom in the limelight.

Jewett also understood the potential of finding new forums through which to expand the reach of the novel beyond Stowe’s text. For further promotion, he hired the poet John Greenleaf Whittier to write a poem, “Little Eva: Uncle Tom’s Guardian Angel,” and then had the composer Manuel Emilio set Whittier’s lyrics to music.

But even outside of Jewett’s savvy publicity tactics, Uncle Tom’s Cabin seemed to spur its own promotion, to an astounding extent. Jewett’s effort at selling branded products—what has come to be called merchandising—ultimately constituted a small portion of the massive proliferation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin spin-offs produced without his or Stowe’s knowledge or consent. Indeed, within months of the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, J.S. Dwight’s prominent music journal grumbled that every music publisher had to make his own “Little Eva” song, with composers paying more attention to song titles than to the quality of the music: “all the minor composers are as busy on this theme, as if it were the one point of contact for the time being with the popular sympathies.”[xix] If not the only point of contact with the popular sympathies, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was certainly the most efficient means of accessing them. It provided a foundation of ready popularity, on which any other creator or manufacturer could build.

Perhaps most importantly, the novel’s fast-moving, multi-threaded plot, its archetypal characters, and its panoramic scope made it a uniquely rich source for adaptation and translation, suited to any genre and attractive to all audiences. Those interested in riding the wave of the novel’s popularity found that it offered a treasure trove of source material: romance and violence, comedy and tragedy, happy families and those torn apart, angels and demons, convention and radicalism. And these elements could be selectively plucked and re-imagined in a vast number of ways: moral theater for church groups, minstrel shows for audiences looking for a laugh, playing cards for children, porcelain figurines for display in parlors, fine paintings and sculptures for art collectors.

With the spread of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, people from every walk of life and from all over the world wept in sympathy for the cruel plight of black slaves, from the working class Frenchman who bought his bread at an Uncle Tom bakeshop to British royalty like the Earl of Shaftesbury, who announced himself a fan. George Sand’s breathless review of the novel proclaimed, “This book is in all hands and in all journals. It has, and will have, editions in every form; people devour it, they cover it with tears. It is no longer permissible to those who can read not to have read it.”[xx] Uncle Tom’s Cabin became not only the best-selling book of the nineteenth century after the Bible, but also the first great American success in the international cultural marketplace. The novel’s centrality to the coming of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery was suggested by none other than Abraham Lincoln, who was rumored to have said, upon meeting Stowe, “So this is the little lady who wrote the book that started this great war.”[xxi]

But the novel’s political impact reached far beyond the issue of slavery, to the very humanity of African-Americans. Although others had argued for the equality of the races, most notably Frederick Douglass, who presented himself as a prime example of black achievement, Uncle Tom was the first black hero in American literature to capture the minds and hearts of a large audience. George Eliot, for one, wrote that Stowe had “invented the Negro novel,” meaning not that Stowe was the first novelist to include black characters, but rather that she was the first one to take them seriously as human beings.[xxii] Uncle Tom, in his colossal popularity, launched the first major national conversation about the humanity of African-Americans.

The immense cultural power of Uncle Tom’s Cabin was immediately obvious not only to abolitionists, but also to pro-slavery Americans, who worried that the novel, with its instant popularity and sympathetic readership, would help bring on the abolition of slavery. To counter Stowe’s attacks, advocates of slavery responded with their own ideological breed of fiction. “In order to meet the fallacies of this abolition tale, it would be well if the friends of the Union would array fiction against fiction,” reasoned the New York Mirror. “Meet the disunionists with their own chosen weapon, and they are foiled.”[xxiii] Within a few months of the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a Southern writer came out with Life at the South: Uncle Tom’s Cabin As It Is in order to set the slavery record straight. Several more anti-Tom texts followed; The Independent counted eight within six months, noting that Stowe’s novel seemed to have produced a whole new school of literature from both sides of the slavery debate.[xxiv] Before Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Southern plantation novels had concentrated on the lives of the white planters, with blacks appearing only in bit parts. But Stowe’s novel brought them front and center, and lastingly so.[xxv] With the popularity of her novel, Stowe had set up a cultural battleground upon which the nature of both the institution of slavery and of African-Americans would be hotly contested for many years to come.

[i] “The Uncle Tom Epidemic,” The Literary World (New York), Dec. 4, 1852, 355.

[ii] André Schiffrin, The Business of Books (London: Verso, 2001), 8.

[iii] “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” Christian Parlor Magazine, May 1, 1852.

[iv] For more on the enactment and enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act, see Stanley Campbell, The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968).

[v] Joan D. Hedrick, Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 204.

[vii] Ronald J. Zboray, A Fictive People: Antebellum Economic Development and the American Reading Public (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

[ix] Claire Parfait, The Publishing History of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1852-2002 (Hampshire, England: Ashgate, 2007), 34.

[x] In the insider’s world of mid-nineteenth-century American publishing, magazines and newspapers usually gave positive notices to publishers and authors who had influence, paid for advertisements, or sent handsome review copies. Those who did not were punished with negative reviews or total silence. See William Charvat, “James T. Fields and the Beginnings of Book Promotion, 1840-1855.” The Profession of Authorship in America, 1800-1870: The Papers of William Charvat, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1968).

[xi] Parfait, The Publishing History of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

[xiii] “Extraordinary Demand for ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,’” The Liberator (Boston), April 9, 1852.

[xiv] “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” The Independent (New York), May 13, 1852.

[xv] “Literary,” The Independent (New York), June 10, 1852.

[xvi] “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” The National Anti-Slavery Standard. August 19, 1852.

[xvii] See Katharine Q. Seelye, “Lurid Numbers on Glossy Pages! (Magazines Exploit What Sells),” The New York Times, February 10, 2006.

[xix] “Eva’s Parting,” Dwight’s Journal of Music, July 31, 1852.

[xx] George Sand, “Review of Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” La Presse, Dec. 17, 1852.

[xxi] This anecdote is often repeated, but possibly apocryphal, as there was no report of such an exchange until much later, in Charles Edward Stowe’s 1889 biography, A Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe.

[xxii] George Eliot, “Review of Dred,” The Westminister Review 10 (October 1856): 571-73.

[xxiii] Reprinted in The Liberator, June 11, 1852.

[xxiv] “Uncle Tom Literature,” The Independent, Sept. 30, 1852.

[xxv] William Taylor, Cavalier and Yankee: The Old South and the American National Character (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979).