Transcription of Chapters 36 and 37

Chapter XXXVI.

“No matter with what solemnities he may have been devoted on the altar of slavery, the moment he touches the sacred soil of Britain, the altar and the god sink together in the dust, and he stands redeemed, regenerated, and disenthralled, by the irresistible genius of Universal Emancipation.”

A while we must leave Tom in the hands of his captors, while we turn to pursue the fortunes of George and his wife, whom we left in friendly hands in a farm-house on the road-side.

Tom Loker we left groaning and tousling in a most immaculately clean Quaker bed, under the motherly supervision of Aunt Dorcas, who found him to the full as tractable a patient as a sick bison.

Imagine a tall, dignified woman, whose clear muslin cap shades waves of silvery hair, parted on a broad, clear forehead, which overarches thoughtful gray eyes—a snowy handkerchief of lisse crape is folded neatly across her bosom, her glossy brown silk dress rustles peacefully as she glides up and down the chamber.

“The devil!” says Tom Loker, giving a great throw to the bedclothes.

“I must request thee, Thomas, not to use such language,” says Aunt Dorcas, as she quietly re-arranges the bed.

“Well, I won’t, granny, if I can help it,” says Tom; “but it’s enough to make a fellow swear—so cursedly hot.”

Dorcas removed a comforter from the bed, straightened the clothes again, and tucked them in, till Tom looked something like a chrysalis, remarking as she did so:

“I wish, friend, thee would leave off cursing, and think upon thy ways.”

“What the devil should I think of them for?” says Tom. “Last thing ever I want to think of. Oh, dear me!” and Tom flounced over, untucking and deranging everything, in a manner perfectly frightful to behold.

“That fellow and gal are here, I spose,” said he, sullenly.

“They are so,” said Dorcas.

[Continue reading the full text of chapters 36 and 37, here.]

Commentary by Jo-Ann Morgan

Associate Professor in the Department of African American Studies and the Department of Art at Western Illinois University

Harriet Beecher Stowe was at the height of Christian persuasion with the March 4, 1852 installment of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” for The National Era. Later, when pictures were added, they too sounded inspirational tones.

True to Stowe’s evangelical intent, chapters 36 and 37 rejoice at pinnacle moments in the lives of several of her main characters. Eliza, with husband George and son Harry, breathe the sanctified air of freedom as they reach Canada at last. Meanwhile, down in Louisiana, Uncle Tom suffers through his darkest hour of southern bondage, wrestling with his strength of faith as he struggles to awaken the best in a desperate slave woman named Cassy.

Of the full-page illustrations Hammatt Billings’ created for the original 1852 John P. Jewett published book version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, touted in advertisements as “six elegant designs,” those related to events of serial chapters 36 and 37 most emphasize themes of salvation and redemption. Billings had relied on Christian iconography earlier in the book. In his print captioned “Eliza comes to tell Uncle Tom that he is sold, and that she is running away to save her child,” the young mother cradles her son in a manner recalling a Madonna and child of Renaissance paintings. An un-inked area of bare page surrounding the slave’s head in his drawing of “Little Eva and Uncle Tom in the Arbor” may seem predictive of a halo for the eventual martyr he will become.

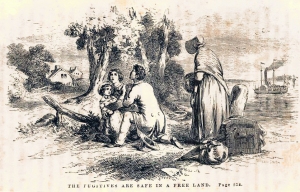

For Eliza and George’s triumphant liberation, consummated at the end of chapter 36, Stowe relies on a convention of American literature dating at least from pre-republic years. Puritan Mary Rowlandson, released from Indian captivity in 1682, had fallen to her knees in gratitude. “Thus hath the Lord brought me and mine out of that horrible pit, and hath set us in the midst of tender-hearted and compassionate Christians,” she wrote. Thanking the almighty for deliverance, bodily and otherwise, was requisite for the Harris family too. After fleeing slaveholder captivity, “the new-made freeman and his wife knelt down, and, with their wondering child in their arms, returned their solemn thanks to God,” exalted Stowe.

Billings’ image of “The fugitives safe in a free land” is also heir to Christian expressive traditions. (Fig. 1) European fine art was rich with prayerful supplicants. In American anti-slavery imagery of the early nineteenth century, the kneeling slave, hands raised in prayer, eyes heavenward had become emblematic of the movement.

[Continue reading the full text of Jo-Ann Morgan’s commentary here.]

How did Stowe connect this chapter to real-life stories? Find out here!

Check out the top news stories, this week in 1852, here!

Leave a comment